Few technologies generate as much debate—or as much potential—in the global race to decarbonize as nuclear energy. It’s clean, reliable, and independent of weather or season. Yet, in today’s energy landscape, nuclear is struggling to compete.

This isn’t a failure of nuclear—it’s a reflection of how remarkably cost-effective solar, wind, and storage have become, increasingly squeezing nuclear out of the economic equation.

Renewables Rising

Over the past decade, renewable energy has surged forward.

Solar panels have become dramatically cheaper, more efficient, and widely deployed. Wind power has expanded across continents, and battery storage technologies are evolving rapidly. Together, these advances have fundamentally reshaped the economics of electricity generation—lowering costs and accelerating decarbonization.

We’re beginning to see the contours of a future energy system that is both clean and affordable. But this rapid transformation is not without trade-offs. One of them is that nuclear energy—despite its reliability and low-carbon profile—is increasingly being squeezed out of the market.

Negative electricity prices, once considered rare, are now a recurring feature in many markets. As renewable generation continues to grow and battery storage deployment takes time to scale, oversupply during periods of high solar and wind production will persist. In such a context, nuclear plants—designed to run continuously at high capacity—struggle to stay economically viable.

The recent, abrupt leadership change at EDF, the world’s largest nuclear power producer, underscores this tension. It’s a clear signal: finding a sustainable financial model for nuclear is becoming increasingly complex in a system built around variable renewables and marginal pricing.

The Nuclear Dilemma

Nuclear power thrives on consistency. It needs high capacity factors and near-perfect availability to remain financially viable. Unlike solar and wind, it doesn’t scale down easily. A nuclear plant that runs only part of the time is an economic disaster.

Historically, European Union regulations have granted priority access to the electricity grid for renewable energy sources to promote their development. This approach was formalized in Directive 2009/28/EC, which mandated that Member States ensure priority or guaranteed access for electricity produced from renewable sources . Specifically, Article 16(2)(c) of the directive states that Member States shall take appropriate steps to ensure that electricity from renewable energy sources has priority access or guaranteed access to the grid system. This legal framework was designed to facilitate the integration of renewables into the energy market, supporting the EU’s goals for sustainable energy production. That made sense at the time. But now, with renewables becoming the dominant force in new capacity additions, it may be time to rethink the rules.

If we want to keep nuclear in the mix—and we should—then it must be allowed to operate in a system that doesn’t penalize it for being constant.

A Fragile Ecosystem

Beyond economics, there’s another critical dimension: the nuclear supply chain and knowledge base. Nuclear is not plug-and-play. It relies on a highly specialized industrial ecosystem—engineers, regulators, safety experts, manufacturers of components and fuels—that takes decades to build and moments to lose.

Today, the nuclear sector supports over 1.1 million jobs across the European Union , spanning operations, construction, research, and manufacturing. In the UK alone, the civil nuclear supply chain employs nearly 87,000 people. These figures illustrate not just an energy source, but a deeply embedded industrial fabric.

Unlike wind or solar, where rapid scale-up is possible from a broad and flexible supplier base, nuclear demands continuity. If civilian nuclear projects decline too much, can military or research programs alone preserve the full depth of expertise and supply chain capabilities?

It’s unlikely. Letting civilian nuclear infrastructure fade may mean losing the option altogether in the future—just when we might need it most.

Strategic Sovereignty and Nuclear Expertise

The war in Ukraine, renewed tensions in the Middle East, and a shifting global security landscape have all reinforced a hard truth: energy and defense are two sides of the same sovereignty coin.

While the civilian nuclear debate often centers around electricity economics and emissions, the strategic dimension of nuclear technology cannot be ignored. Nuclear deterrence remains a core element of security policy for several European states and NATO as a whole. But nuclear deterrence isn’t just about the warheads—it’s also about the people, the infrastructure, and the industrial capacity behind them.

Maintaining a sovereign nuclear deterrent or participating in shared security frameworks requires more than military doctrine. It requires a robust, local ecosystem of nuclear engineers, physicists, regulatory experts, and manufacturers. These are the same capabilities that underpin the civilian nuclear sector. If we let them erode in times of peace, we may not be able to rebuild them in times of crisis.

Civilian nuclear infrastructure plays a quiet but crucial role in strategic resilience. By continuing to invest in and protect these capabilities, Europe not only secures part of its energy transition—it also reinforces its geopolitical autonomy in an increasingly unstable world.

A Millefeuille Energy System

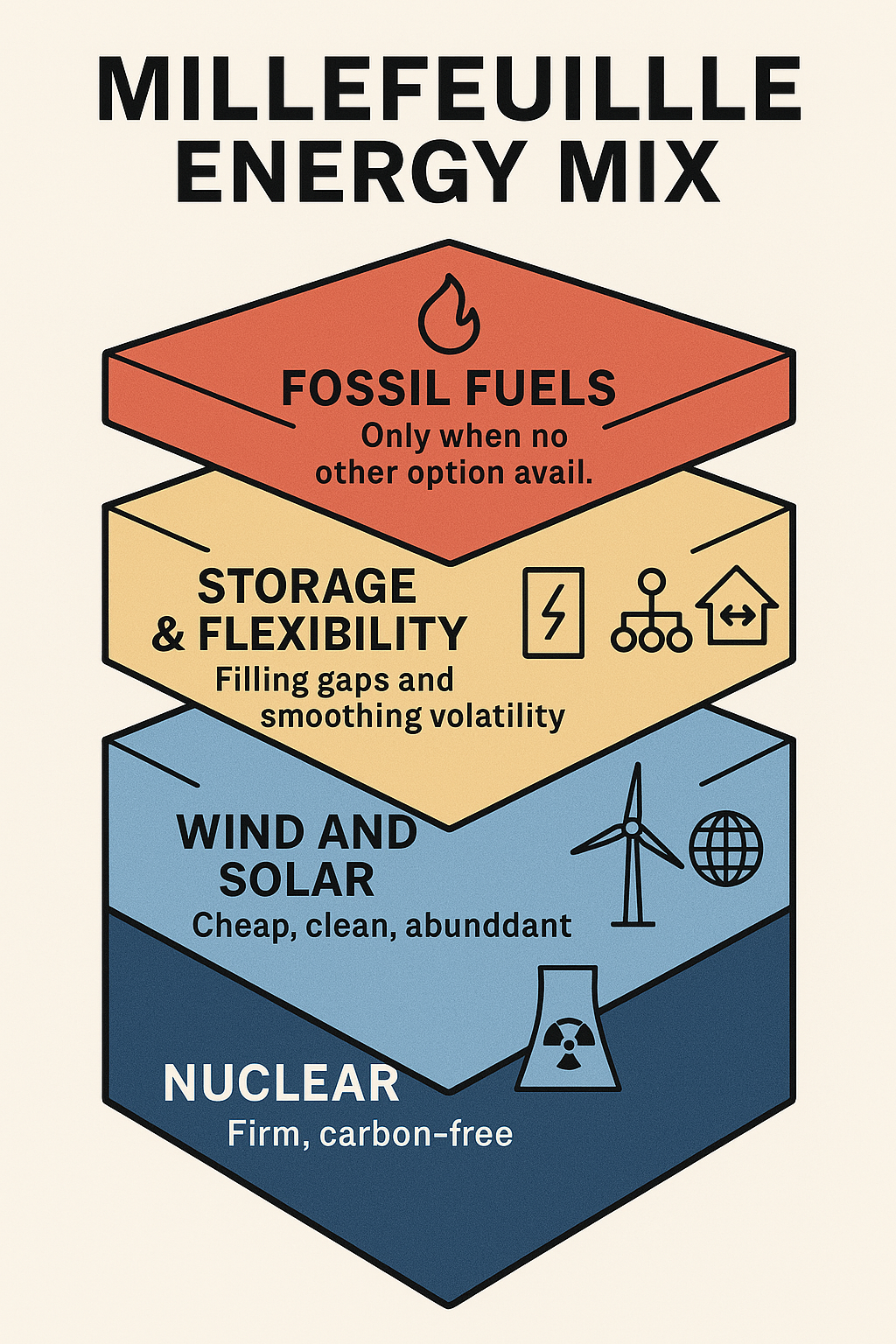

The future of energy isn’t about picking winners. It’s about orchestrating a mix—a layered system, like a millefeuille, where each technology plays its part based on its strengths.

- Nuclear: the base layer—firm, stable, and carbon-free. It should get first priority, ensuring reliability and maintaining critical industrial capabilities.

- Wind and solar: the renewable middle—cheap, clean, and abundant. They deserve priority access, but must be balanced within the broader system.

- Storage & Flexibility: the glue between layers—filling gaps and smoothing volatility. This includes not just batteries, but Virtual Power Plants (VPPs), flexible loads, and demand-side response mechanisms that absorb excess generation and shift consumption in time to stabilize the grid.

- Fossil fuels: the top layer—used only when no other option is available, and priced accordingly.

This isn’t just a metaphor—it’s a roadmap. A well-structured millefeuille of technologies can deliver decarbonization, affordability, and resilience. But like any fine pastry, it needs careful layering, regulatory finesse, and long-term vision.

We don’t need nuclear to lead the energy transition—but we do need it to be there when we need it most..

The Limits of the Market

The truth is, market forces alone seem unable to give nuclear energy its rightful place in a cost-optimized, low-carbon energy system. Nuclear may not need to dominate—but it may very well need regulatory support simply to survive, especially in an era of rising energy demand driven by the AI boom.

That support, however, must come with a clear and pragmatic purpose: not to pursue nuclear at any cost, but to ensure that it plays a meaningful role in reducing the overall system cost for consumers. Granting nuclear the highest level of priority on the network could be justified—but only if its share is intentionally capped, to avoid distorting market signals or driving up electricity prices.

System vs. Market

| Priority Level |

System Logic (Resilience-Based) / Proposed |

Market Logic (Price-Based) / As of today |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Behind-the-meter generation, storage, optimisation | Behind-the-meter generation, storage, optimisation |

| 1 | Nuclear – Stable, carbon-free baseload for long-term and seasonal reliability | Wind & Solar – Zero marginal cost; always dispatched first under market rules |

| 2 | Wind & Solar – Cost-effective, clean bulk power; variable but increasingly dominant | Clean Energy Tariffs – These are not integrated in dispatch logic and only indirectly affect consumer behavior. Tariffs are still fossil fuel-centric. |

| 3 | Clean Energy Tariffs – Time-of-use, dynamic pricing, and carbon-indexed tariffs to shape demand | Nuclear – Low marginal cost but inflexible; often uneconomical during oversupply |

| 4 | Grid-Scale Storage – Short- and long-duration storage for smoothing volatility and shifting energy | Grid-Scale Storage – Operates on price arbitrage; not system-optimized |

| 5 | VPPs & DSR – Aggregated flexibility from buildings, EVs, and industry | VPPs & DSR – Poorly compensated or invisible in current market structures |

| 6 | Natural Gas – Dispatchable backup for rare events or long renewable lulls | Natural Gas – Dispatchable; frequently sets marginal price in real markets |

| 7 | Coal / Emergency Imports – Last-resort backup to avoid system failure | Coal / Lignite – Still used in some markets; low cost where carbon pricing is weak |

This table highlights the growing divergence between how energy systems should be designed for resilience and decarbonization, versus how they are currently shaped by market rules

- On the left, System Logic reflects a layered, strategic approach. It values stability (nuclear), clean bulk power (wind & solar), flexibility (VPPs, DSR, storage), and behavioral alignment (tariffs) in a way that minimizes overall system costs and emissions.

- On the right, Market Logic ranks resources by marginal cost and dispatchability. While this promotes short-term efficiency, it often under-rewards flexibility, penalizes inflexible baseload like nuclear, and gives limited economic value to behavioral signals or system-wide resilience.

The result? The very technologies that could optimize the grid long-term are often marginalized or mispriced.

To bridge this gap, market reforms must recognize and internalize system-level externalities—rewarding flexibility, clean capacity, and demand shaping, not just marginal energy cost.

A Pragmatic Path Forward

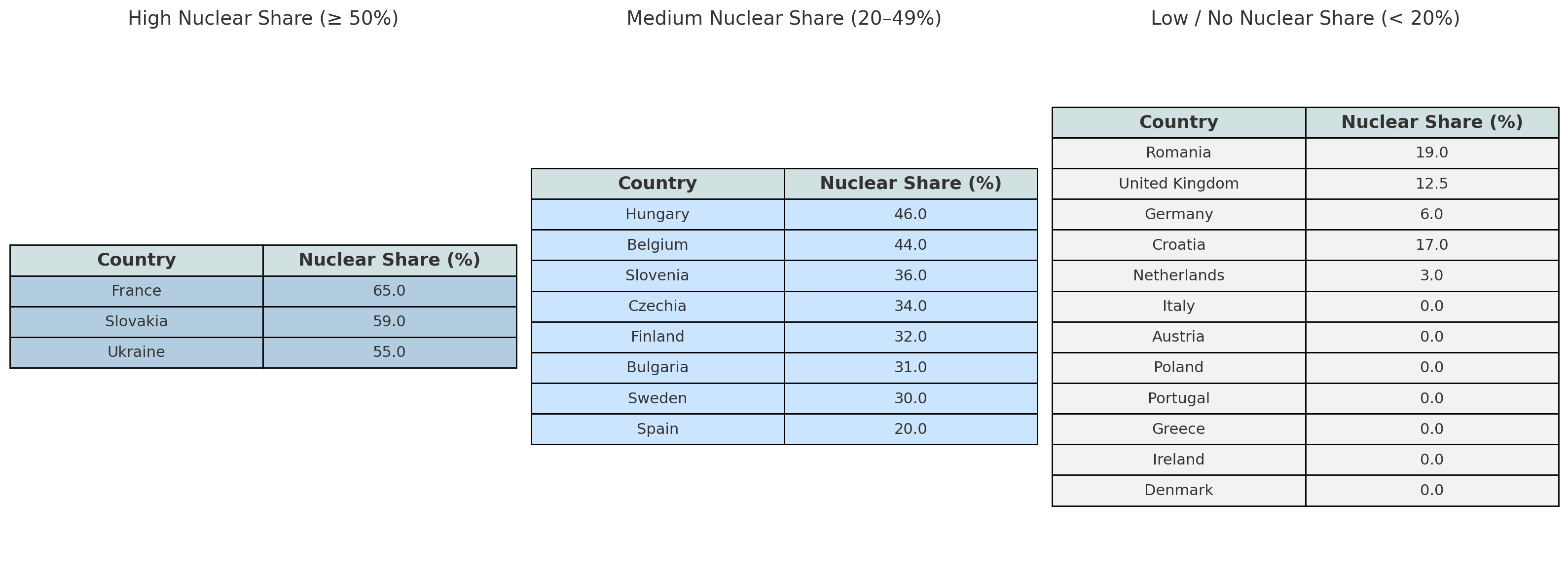

Whether nuclear should account for 5%, 10%, or 20% of Europe’s future electricity mix—it currently stands at around 22% of EU electricity generation—remains an open and country-specific question. What seems increasingly clear, however, is that targeting much higher penetration across the EU, as some in the nuclear lobby advocate, may be unrealistic—and even counterproductive.

Instead, establishing a realistic, enforceable cap on nuclear’s role in the European energy mix, alongside the highest level of network priority, may offer a way forward: preserving a vital industrial and strategic capability while keeping system costs in check. It could be the balanced path that allows nuclear energy to endure and contribute, without distorting the economics of the broader energy transition.

It is also a deal that could unite both renewable energies advocates and nuclear energie advocates and create a winning coalition for electrification and the energy transition

It is time for France and Germany to find common ground on this issue—one that has remained unresolved for far too long. An abundant supply of clean, affordable energy is not a luxury but a strategic asset for Europe’s future. While each Member State will continue to shape its own national energy agenda, the EU urgently needs a clear, pragmatic roadmap that enables the coexistence and complementarity of renewables and nuclear power . Without such alignment at the European level, the energy transition risks becoming fragmented, inefficient—and ultimately much more expensive for European consumers.